ARTICLE: 5 Activities to Really Engage Readers

We want our students to be reading closely and thinking deeply. Here are five adaptable ideas that keep students creatively interacting with texts.

Dear paid subscribers: Thank you! You’re providing essential support that helps MiddleWeb.com continue our commitment to publish the voices of middle grades educators – and to update and curate our thousands of articles and reviews written for and by educators who support kids in grades 4-8.

If you are a free subscriber, we could really use your help; consider a paid subscription when you can. ($5 month; $50 year).

All our subscribers receive our free biweekly newsletter showcasing teaching and leading topics you care about. What follows here is one of the occasional full-text articles we share, plucked from a list of all-time popular posts.

★ MiddleWeb Substack Full-Text Article ★

5 Adaptable Activities That Really Engage Readers

By Marilyn Pryle

With the start of the new school year, we are always looking for new activities to freshen up our repertoire! At the same time, we want our students to be reading closely and thinking deeply. Here are five adaptable ideas that you can add to your toolbox to keep students creatively interacting with texts.

1. Quote Give Away

I like to use this as a prereading activity, especially with well-known authors: Have students get acclimated to the author’s style by searching through brief quotes from the author.

► Examples of quotes include:

Rumi: What you seek is seeking you.

Lois Lowry: Take pride in your pain; you are stronger than those who have none,

Shakespeare: Words are easy, like the wind; faithful friends are hard to find.

Quotes can easily be found through a simple Google search or even just through Goodreads.com. I have students find three quotes:

One that has meaning for themselves

One that has meaning for a family member, friend, or mentor outside class

One that has meaning for a classmate who will be randomly assigned

I randomly pair students (for #3 above) and give them class time to interview each other. This way, even if the paired students don’t know each other well, they will have some information to begin their quote searches. (Note the listening and speaking elements here as well.) The other two quotes—one for themselves (#1) and one for a family member, friend, or mentor outside class (#2)—don’t require interviews.

Students then have a few days to locate their appropriate quotes and put each on a separate piece of paper and decorate. The quotes can be turned into bookmarks, locker signs, or mini-posters for home as daily positive reminders.

Additionally, students must a write brief note on the back of each quote to the person the quote was selected for. This note should explain why the student chose that particular quote for that person. If you wanted to include more writing for this activity, students could write a longer paper explaining what each quote means and why it was chosen for the particular recipient.

On the due date, students must bring in all three quotes, decorated. While students read or work on another activity, I circulate, check, and admire all quotes and decorations.

Students then meet with their randomly assigned partner to trade the quotes they have prepared for each other.

This step is nothing short of beautiful! Listening to students explain to each other why they selected meaningful quotes from a famous author is a moving experience to watch.

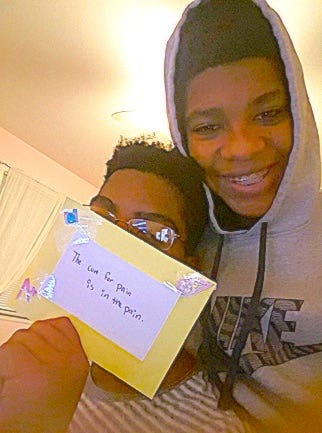

Students obviously keep the quote they prepared for themselves. And they should deliver the quote for person #2 – a family member, friend, or mentor outside class. When I first tried this activity, I wondered about this. How would I know if the quote had really been delivered? The answer: selfies! I gave students an additional three days to deliver their quote and take a selfie as proof. This one says, “The cure for pain is in the pain.”

Students claim they read “hundreds!” of quotes to find ones that would work for each recipient. I love this activity because it incorporates real audiences, audiences the students care about. This makes them read through dozens of quotes intensely, scouring for meaning and testing for application. And the element of giving something away not only creates positive vibes but also communicates the message that literature is a communal event, something to be shared, something that connects us to each other in real and meaningful ways.

2. Character Bucket List

The “Bucket List” is a type of To-Do list. However, it is not a daily, errand-running, responsibilities-are-nagging-at-you kind of To-Do list; it is an end-of-life To-Do list.

To create one for a character, students must imagine that character’s largest goals, interests, and dreams. Students must use not only direct information from the text, but also inferences based on that information.

Character Bucket List Brainstorming Questions:

► What do you think is the greatest thing the character could achieve in life?

► Where in the world would the character want to travel?

► What famous people would the character want to meet?

► What is the ultimate expression of the character’s talents?

► If the character wrote a book, what would it be about?

► What farfetched kinds of experiences could you see this character having?

I recommend setting a minimum number of items for the Bucket List, such as ten. This will ensure that students think past the first few obvious answers.

Extra Challenge: Reason Bubbles. If you wanted to go even more in-depth with the assignment, have students attach a “Reason Bubble” to each item on the bucket list explaining their thoughts.

Extra-Extra Challenge: Page Numbers. Have students cite a page number for each item on their list. The page number could be the literal citation of the item, or it could reference the information that led the student to the inference that created the item. Either way, students must show exactly where in the text their reasoning originated.

3. Host an Event

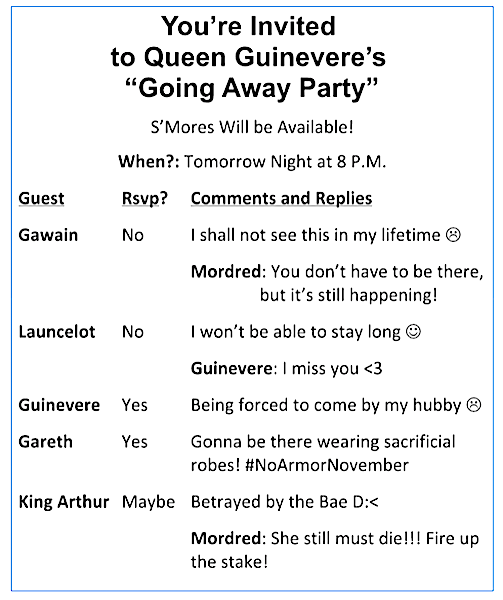

For this activity, you should be familiar with the Evite website, a business that lets people email invitations for an event and manage the replies.

Both guests and host can leave comments on the replies; guests can also add other guests or volunteer to bring items. As I was creating an actual Evite invitation for my own family, I thought of the mythical Eris, goddess of chaos and troublemaking, who was purposefully snubbed for the wedding of Thetis and Peleus, and I mused about how that would play out on an Evite page. I then realized that it would be interesting for any literary character to send out and respond to invitations for an event.

To complete the activity, students must:

► Create an event and decide which character would host it.

Of course, it is possible to use an event that already takes place in the story as well. However, if students must invent an event, they usually come up with creative and humorous ideas which reflect a thorough understanding of the story.

► Create a guest list.

► Figure out who would actually attend, who would not (because of a conflict or other reason) and who is undecided. On the Evite website, guests can respond either “Yes,” “No,” or “Maybe.”

► Have each invited guest leave a comment. This is where it gets interesting. Each guest, whether attending, not attending, or undecided, should leave a comment. The comments need not be long; just a sentence or two could be enough to reveal a character’s true feelings.

Maybe a character is so excited about the event she can hardly contain herself; maybe he tells what he will bring or wear; maybe he leaves a sarcastic remark while declining the invitation; maybe she expresses self-doubt or fear of another character. Students should use explicit and implicit information from the text. They should not write any comment that they cannot defend by pointing somewhere in the text. These comments should run in a list down the page.

► Have guests comment on each other’s comments. Like most social media websites, Evite allows guests to reply to already-posted comments. With that, each guest’s response can become a mini-conversation, going even further to reveal the students’ understanding of the story. Of course, the host can also reply to any posted comment as well. You can have your students write at least one reply to every guest’s initial comment, or, if that seems too overwhelming, have the students reply to just five (or another minimum number) initial comments.

The final page, then, would have the event at the top with a short description underneath, the name of the host, and the list guests, along with their comments and replies. If you choose, you could also have the students decorate the page with a party theme of some kind. It helps to show them a print-out of the actual website, though students are already very familiar with the comment/reply routine.

4. Create a Catalogue

This activity is best assigned towards the end of a longer reading, when students can recognize important objects and symbols throughout a text. Students should create a catalogue of items for sale, just like any other catalogue you would find in the mailbox or online. In doing so, they will reveal the depth of their understanding of the text.

The “items” in the catalogue should include actual objects or real estate from the story, but students can get creative—maybe they want to include a “rare photo” of certain scene or person, or another item that does not literally appear in the story but could have very well existed. To invent items, students will have to infer from the text.

To assemble the catalogue, students should decide which items they will include (it helps if you set a minimum number), order or group them in a logical way, and list them individually. They can include a picture and a description. The description should not only physically explain the item but should also somehow reveal its significance in the story. For fun, students can set a price for each item, further indicating its worth in the text.

Extra Challenge: Cite the Page. As a challenge, you could have students cite each item with a page number from the book. The items which appear in the book can be cited for the page on which they are mentioned. But the “invented” items can also be cited—students should cite the page that gives the information that led to the inference. You could even have students use reason bubbles along the sides of the items to explain their thinking.

Below are some examples from a catalogue based on Lois Lowry’s The Giver.

5. Figurative Language Scavenger Hunt

This handout aims to help students analyze an author’s choice of words, specifically, figurative language. Emphasize to the students that the figurative language in a piece—the similes, metaphors, personification, onomatopoeia, alliteration, and so on—isn’t accidental; the author chooses these particular symbols or sounds in order to reinforce the mood, theme, or plot point.

For example, at one moment in a story, rain could be falling. If it were a safe, happy moment, the author could use the phrase “rain like soft kisses.” If it were an ominous moment, the author might say “rainclouds gathered like menacing ghosts.” If it were a painful moment, the author might use the personification and alliteration of “the drops poked at his skin.” It is important that students learn to recognize these choices, and make guesses at what meaning or mood the author was reinforcing.

The handout above could be used as a post-reading activity with a few pages or entire chapter. Students should skim the section for examples of figurative language, copy them, and cite the page number. This compels them not only to reread for meaning, but also to apply the definitions of various figurative motifs (which they may have learned in isolation) to actual texts. They should also take a guess at why the author chose that particular figurative arrangement.

Keeping students curious and engaged

Offering students a variety of activities helps them dissect texts in new and surprising ways, and most importantly, keeps them interested! I rotate through dozens of pre-, post-, and during-reading activities throughout the year to help students stay curious and engaged. I hope these five ideas help your students interact with texts in new and creative ways as well.

Marilyn Pryle (@MPryle) is a National Board Certified teacher in Clarks Summit, PA and the 2019 Pennsylvania Teacher of the Year. Marilyn has taught middle and high school English for over twenty years. She is the author of several books about teaching reading and writing, including 50 Common Core Reading Response Activities and Writing Workshop in Middle School, both from Scholastic.

Marilyn’s many books include 5 Questions for Any Text: Critical Reading in the Age of Disinformation (Heinemann, 2024) and Reading with Presence: Crafting Meaningful, Evidenced-Based Reading Responses (Heinemann, 2018). Learn more about Marilyn at marilynpryle.com and read other articles she’s written for MiddleWeb.